Part 3 | Designing the New Vertical Landscape

Frank Lloyd Wright | Drafting Table | 1956

Part 3 of 4 | Designing the Mile High

Unpacking all the inscriptions, one will find that the Mile High drawings are not just the design of a building, but a history of architecture. From the Great Pyramids and Eiffel Tower to the Empire State Building, Wright was placing The Illinois in the timeline of grand monuments.

The traditionally landscape hugging architect was accustomed to designing for the horizontal. His career spanned three transformations evolving from the traditional Prairie House he popularized during his early residential career, followed by the Organic Architecture Theories he formulated as his work transitioned into institutional and theoretical landscapes, until finally securing the throne as the world greatest Modernist with the completion of the Guggenheim in New York.

“If we’re going to have centralization, why not quit fooling around and have it”

However through all that time only two skyscrapers were ever built. One in Racine, Wisconsin where Wright first tested the Tap Root system at the Johnson Research Tower, and the second in Bartlesville, Oklahoma with his hybrid commercial residential design for The Price Tower. Neither of which are all that tall. That didn’t limit Wrights imagination from soaring as he felt he had solved all of the nagging structural problems of building tall — and more than a few of the social ones associated with skyscrapers. Wright was confident he was ready.

“If we’re going to have centralization, why not quit fooling around and have it,” he said, reportedly adding "Why not design a building that really is tall? ... Long ago I observed trees after the passing of a cyclone. Those with deep tap roots were the ones that survived."

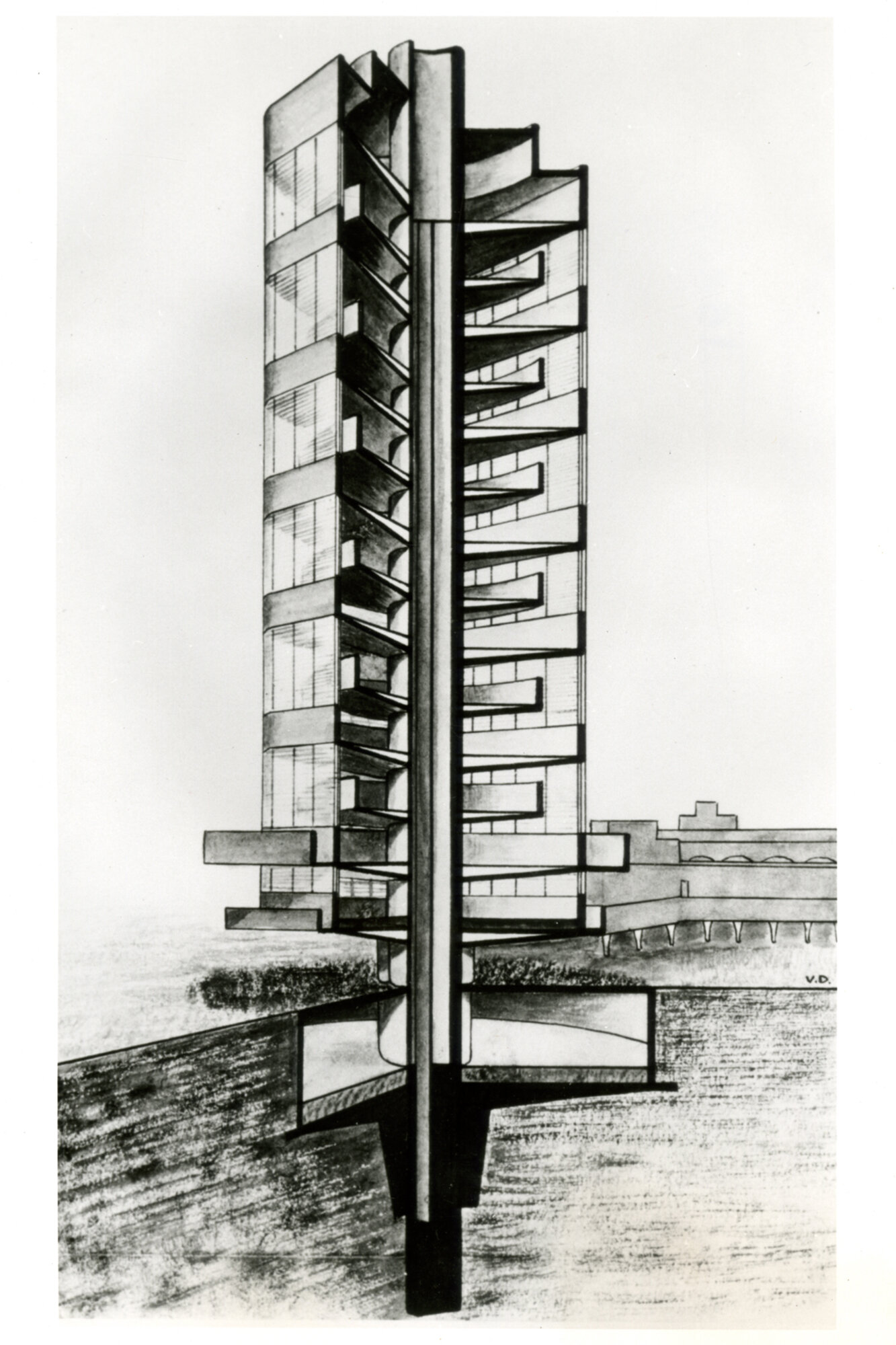

The ‘Tap-root’ structural model he was referring to worked by sinking a central concrete mast deep into the ground then cantilevering floors out from the core like branches of a tree.

In contrast to a typical skyscraper, in which same-size floors are stacked atop of one another using a heavy rigid steel frame or load bearing walls, Wright planned a core that ran up the centre of the entire structure that housed the building’s infrastructure.

This method is best demonstrated by the Johnson Research Tower (above) where the tap-root system let floors vary in size, opening the towers interior and letting space flow between floors through the entire height of the structure. By embedding the tap-root core into the bedrock, the foundation of the ‘Heliolaboratory’, later renamed the Johnson Research Tower, as well as the similar principles used in the foundation system that saved the structure of the Imperial Hotel in the 1922 Japan earthquake, resulting in an unyieldingly rigid structure.

However The Mile-High didn’t intend to just be tall, it aimed to be exceptional tall. Conceived in 1956 when the tallest structure is the world was still the Empire State Building at 1,250 feet (only a quarter of a mile). Even now over a half a century later The Burj Khalifa which opened in January 2010 is still only 2,720 feet tall (half the height Wright envisioned). Many are quick to note that nothing has ever came close to what Wright was proposing, and to date nobody has yet come close to achieving many of the futuristic concepts included in his design.

That’s not to say that the Illinois was entirely unrealistic. It is often acknowledged the striking similarity between the Wrights design and the Burg Khalifa, or that of other exceptional tall structures that were built in the years that followed. Many of which utilize a great deal of the same concepts Wright conceived in his design. From the hexagonal central shaft reinforced by three buttresses that form a Y shape demonstrated with The CN Tower in Toronto to the metal and glass curtain wall system that has became typical of all skyscrapers today.

Mile High Foundation Section Detail. Showing Base and Taproot Structure.

Wright aimed to employ the same system of "tap-root" foundation for the core of the Mile-High and couple it with a tensile metal frame skinning the tower. Wright wrote at the time that ‘the most stable of all forms of any engineered structure is the tripod. For structural stability the Y-formed ‘tripod’ shaft was essential to the Illinois’ assembly.

Mile High Floor Section. Showing Metal and Glass Glazing.

The exterior was to be entirely metal-faced, carried by steel wires suspended from a rigid steel core buried in light-weight concrete. The building is designed from the inside out instead of the outside inward. Throughout this light-weight ‘tensilised’ structure, all members, loads, and cantilevers would be engineered to equilibrium at all points. As a result Wright insisted that ‘there would be no sway or oscillation at the peak of the Illinois’.

Wright was ahead of everyone else adopting innovative building methods and novel solutions that became apart of the collective consciousness of architects and engineers. St Mark's Tower, Crystal Heights, The Price Tower, Johnson Research Tower -- and now The Illinois. Throughout all of them Wright put the same principles to work : a central mast carrying cantilevered floor slabs, metal and glass screen walls and a taproot foundation.

Utopian Rendering of Brandacres City with the Mile High included

In addition to being one of the most innovative architects of his day, Wright also dabbled as an urban planner. He saw design of modern cities as posing a serious problem; they were dense communities overly populated with people who didn’t have enough space to live fulfilling lives.

While the other modernists like Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe were masterplanning dense urban cities and cookie-cutter grids of concrete, glass and steel, Wright was envisioning a broad utopian countryside with pockets of soft density spaced out between urban forests and agricultural land.

In the final years of Wrights life his work took on a more vertical approach to architecture. His friendly battles with Phillip Johnson whom was eagerly ushering in the next generation of Architects, to the multiple failed attempts to convince clients to build outwards had Wright working with more elevator companies than landscapers.

With a few strokes of his pencil, the masterplan for Broadacre City had a monolithic tower extending a mile out from the pristine landscape. Whatever finally caused Wright to rotate his drafting board from horizontal to vertical, it didn’t altar his vision and ideals for an interconnected landscape. Only this time it was a vertical landscape with floors interweaving with escalators, sky lobbies, and cantilevered balconies. This approach made the design of Wright skyscrapers unlike any other architect had produced before, and the foundation of how designers today are looking to resolve the concern of vertical cul de sacs plaguing our current city model.

The Mile-High Handsketch

Credits & Sources

The Wright Library. Sixty Years of Living Architecture: The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright (1951-1956). http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Books/sixty.htm#1956Insert

The Tree That Escaped The Forest. By Frank Lloyd Wright. Published by Horizon Press, N. Y., 1956. https://www.abebooks.com/

The Capital Times. Page 1. Tuesday October 16th, 1956.

Daily World. Page 26. September 21st, 1956.

MOMA. Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. Jun 12–Oct 1, 2017 https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1660

Milestones and Memoranda on the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Vol. 32, No. 4 (Nov., 1956), pp. 361-368

Sixty years of living architecture : the work of Frank Lloyd Wright by Wright, Frank Lloyd, 1867-1959. https://archive.org/details/sixtyyear00wrig/mode/2up

Building Seagram. by Phyllis Lambert.

Architecture: Close Reading; Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mile-High Rise. By Philip Nobel. Oct. 17, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/17/arts/architecture-close-reading-frank-lloyd-wrights-milehigh-rise.html