Johnson Research Tower and Administration Building marks Frank Lloyd Wright entry into the Vertical Landscape.

Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most influential architects of the 20th century, was renowned for his philosophy of 'organic architecture.' This principle emphasized harmony between human habitation and the natural world, a concept that Wright extended to his approach to vertical design. Wright's innovative use of elevators, particularly in the Johnson Research Tower, marked a significant shift in architectural design and functionality for the landhugging architect.

Wright's architectural philosophy was rooted in the belief that buildings should be in harmony with humanity and its environment. This belief extended to his approach to vertical design, where he saw the potential for buildings to rise gracefully into the sky, rather than sprawling horizontally across the landscape. Wright's vision for vertical architecture was not merely about height; it was about creating a seamless integration between the building and its surroundings, even when that meant challenging traditional architectural norms.

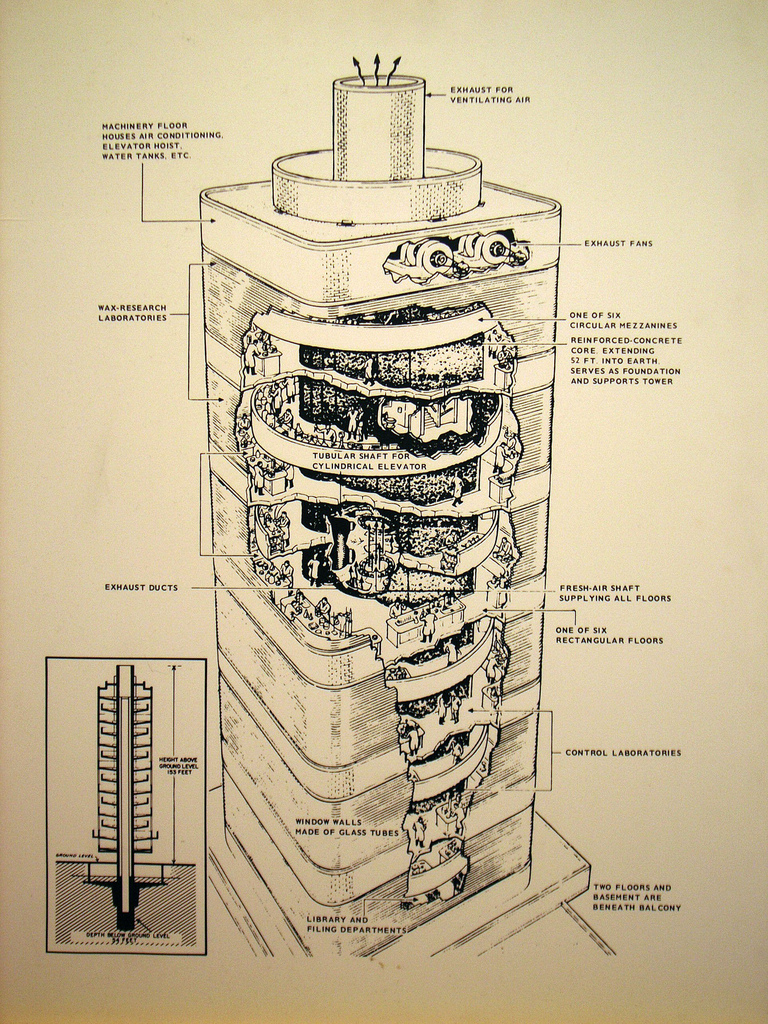

Wright's incorporation of elevators into his designs was a testament to his innovative approach. He recognized that elevators were not just a means of moving people from one floor to another; they were a critical component of the building's design and functionality. In the Johnson Research Tower, for example, the elevator was central to the building's design, both literally and figuratively. It was located in the center of the building, providing easy access to all floors and facilitating the movement of people and materials.

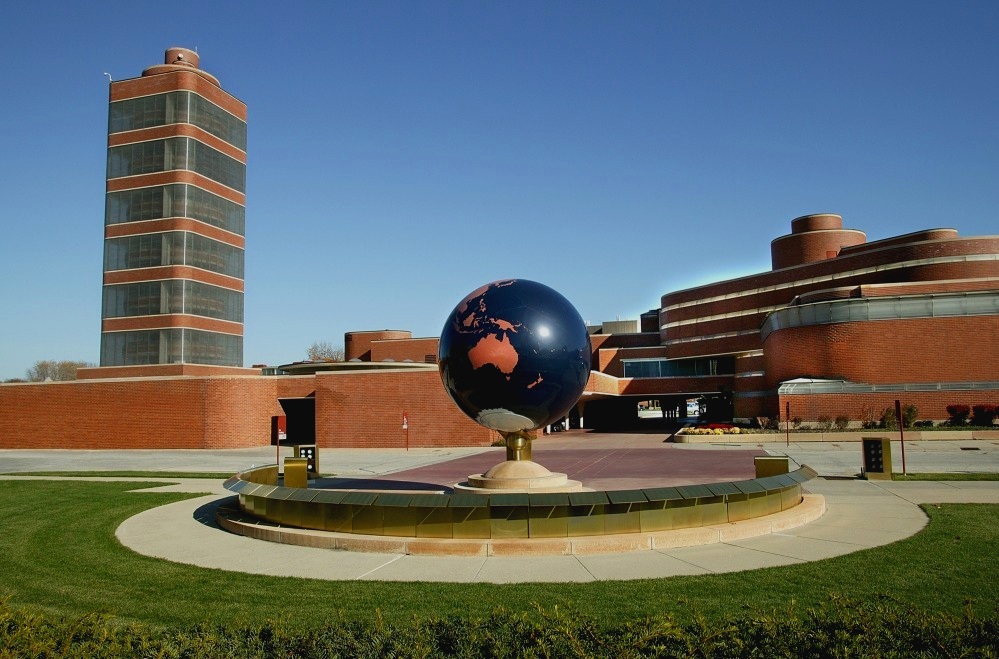

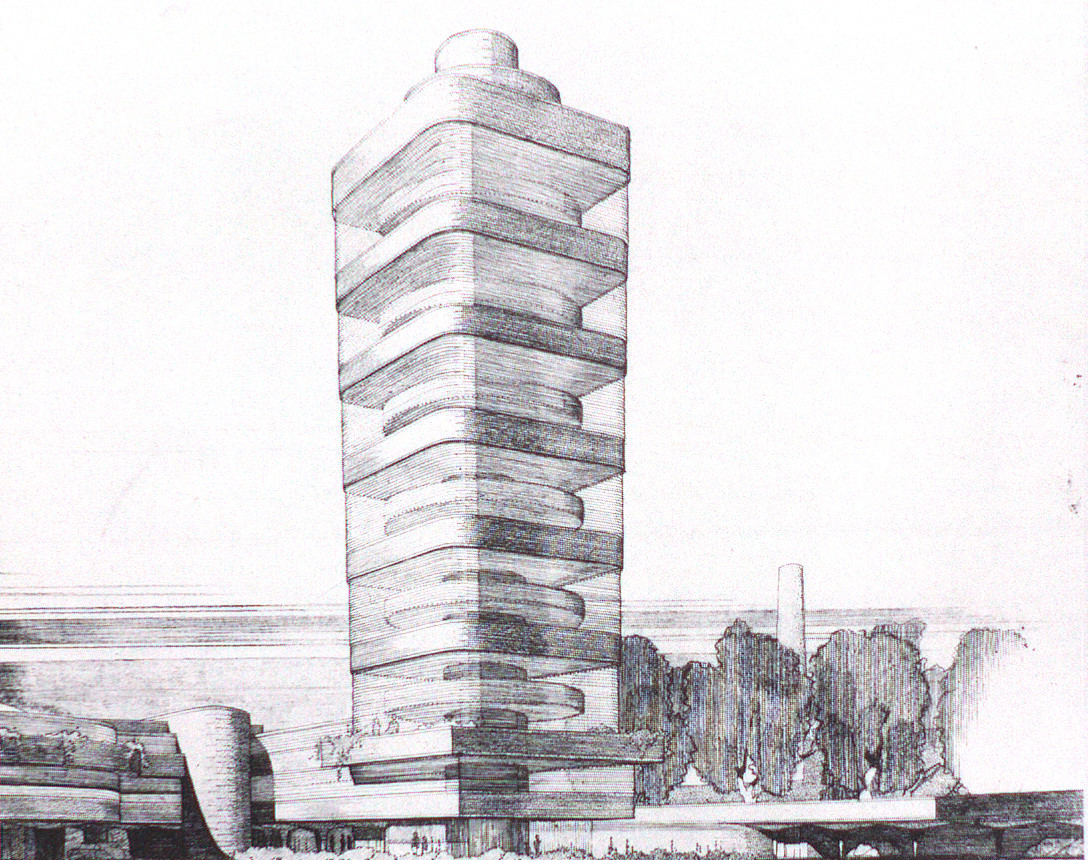

The Johnson Research Tower, completed in 1950, stands as a testament to Wright's vision for vertical architecture. The 14-story tower, part of the SC Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin, was one of the first buildings to use Pyrex glass tubing in its construction, a material choice that was both innovative and controversial.

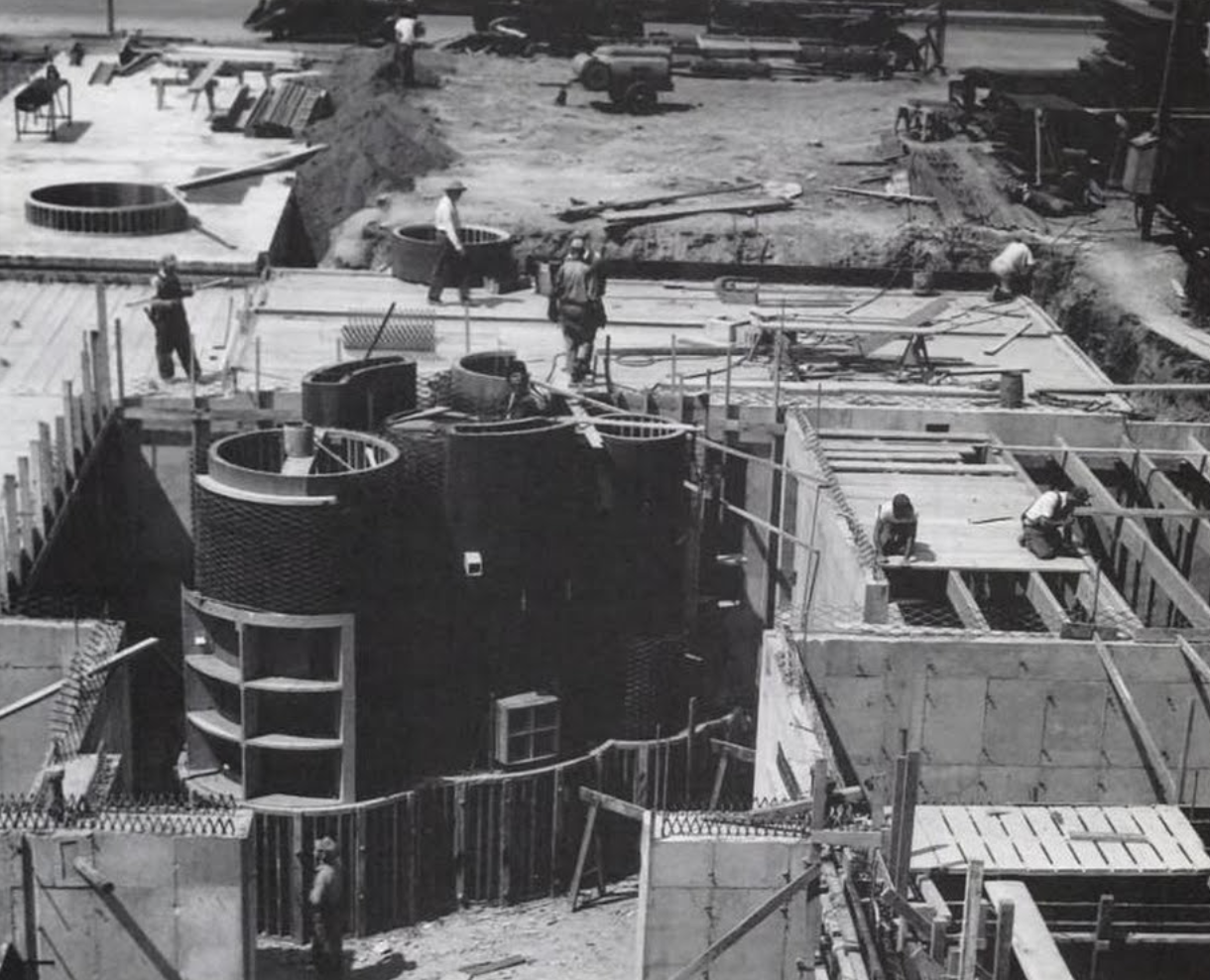

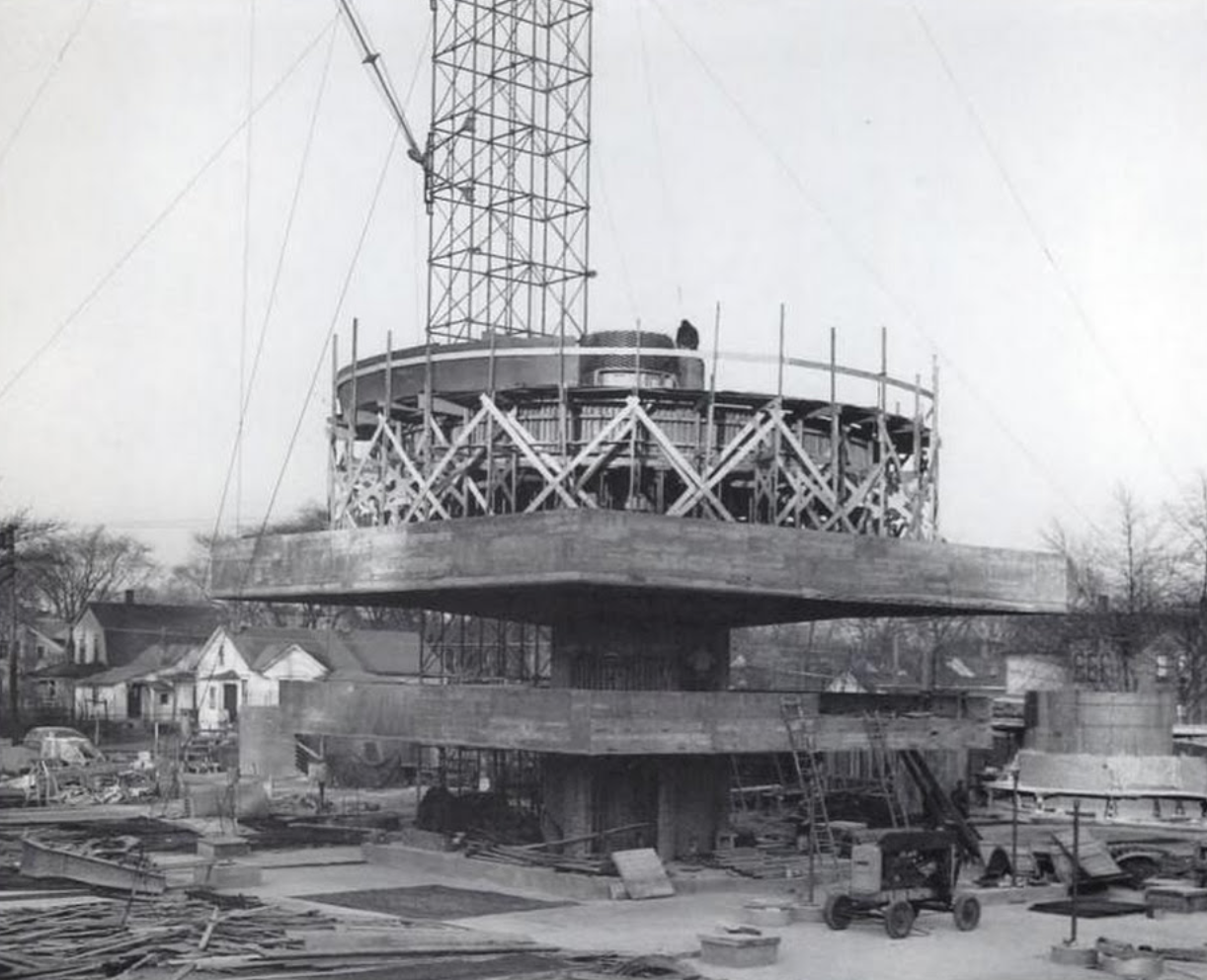

The design of the Johnson Research Tower was unique, reflecting Wright's commitment to integrating form and function. The building's circular floor plan, combined with the central location of the elevator shaft, allowed for a seamless flow of movement throughout the building. The elevator itself was custom-made to fit the unique design of the building, and its installation was a significant engineering feat.

The elevator's impact on the Johnson Research Tower was profound. It not only facilitated the building's functionality but also contributed to its aesthetic appeal. The elevator shaft, encased in glass, became a visual focal point of the building, symbolizing the building's innovative design and its connection to the vertical landscape.

Moreover, the elevator played a crucial role in the building's status as a research and development facility. It enabled the vertical movement of people and materials, making it possible for the building to function as a dynamic, multi-level workspace.

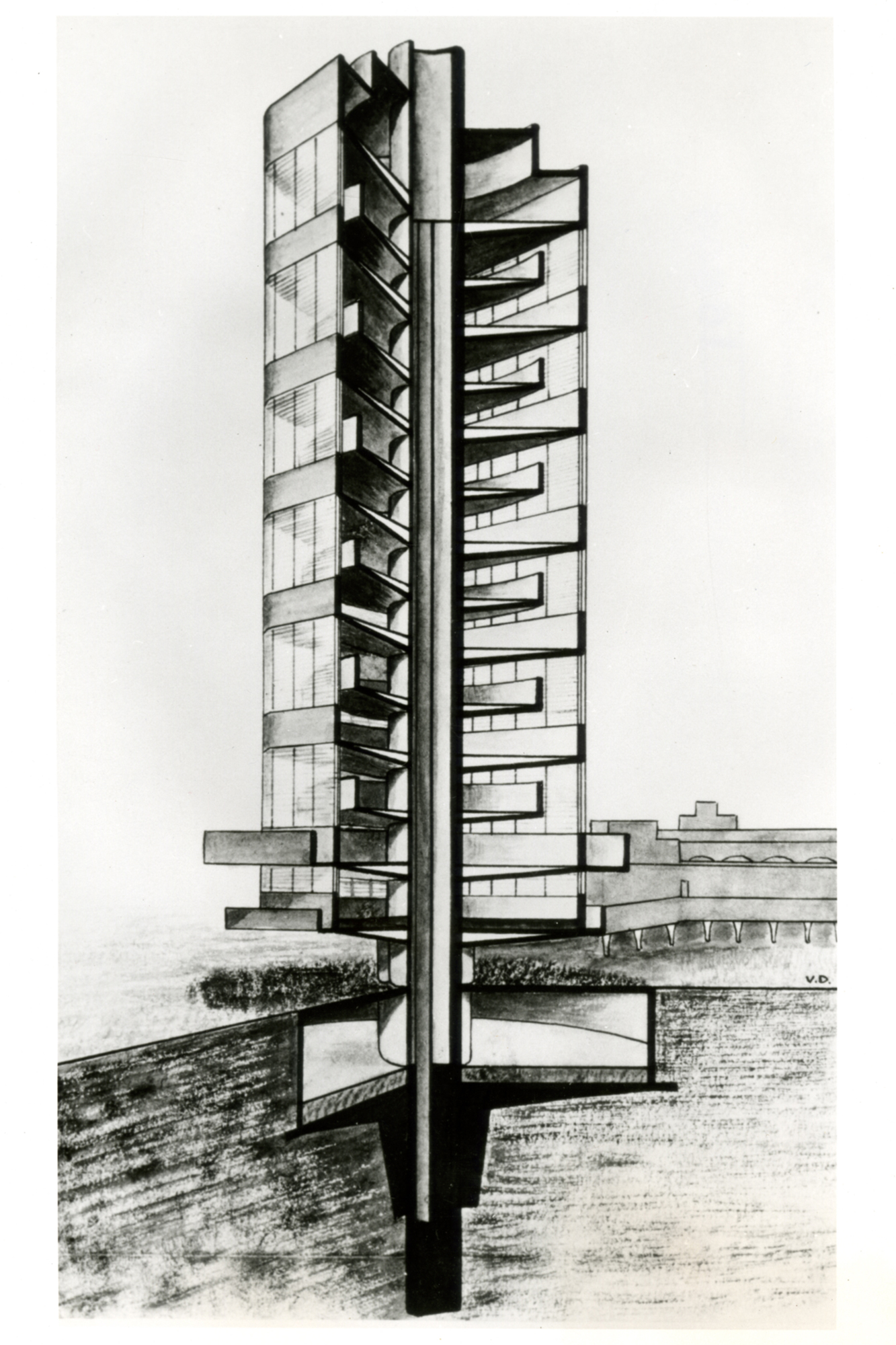

The Research Tower was a later addition to the building, and provides a vertical counterpoint to the horizontal administration building. Alternating square floors and round mezzanine levels make up the interior, and are supported by the “taproot” core, which also contains the building’s elevator, stairway and restrooms.

The tower is one of only 2 built high rise buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright. The core extends 54' feet into the ground, providing stability like the roots of a tall tree. The tower's floor slabs spread out like tree branches, providing for the segmentation of departments vertically.

“Long ago I observed trees after the passing of a cyclone. Those with deep taproots were the ones that survived." The ‘Taproot’ structural model he was referring to worked by sinking a central concrete mast deep into the ground and cantilevering floors from the mast like branches of a tree. In contrast to a typical skyscraper, in which same-size floors are stacked atop of one another using a heavy rigid steel frame or load bearing walls, Wright planned a core that ran up the centre of the entire structure that housed the building’s infrastructure.

“Alternating square floors and round mezzanine levels make up the interior, and are supported by the “taproot” core, which also contains the building’s elevator, stairway and restrooms.”

This concept was best demonstrated here in the Johnson Research Tower where the taproot system let floors vary in size, opening a the towers interior and letting space flow between floors. Consisting of 15 floors, the tower is supported by the central core, or taproot that extends 54 feet into the ground.

The walls around the slabs are created with 5,800 Pyrex glass tubes, lined with bands of more than 21,000 Cherokee Red bricks.

In 1976, the building was designated as a National Historic Landmark. The Research Tower is no longer in use because of the change in fire safety codes (it has one 29-inch wide twisting staircase), although the company is committed to preserving the tower as a symbol of its history and maintains it and all its parts.

In 2013, an extensive 12-month restoration was completed. The research labs shown on the tour has been set up to appear frozen in time, including beakers, scales, centrifuges, archival photographs and letters about the building.

Frank Lloyd Wright's innovative use of elevators in his designs, particularly in the Johnson Research Tower, marked a significant shift in architectural design and functionality. The elevator was not just a means of moving people from one floor to another; it was a critical component of the building's design and functionality. Wright's vision for vertical architecture, as embodied in the Johnson Research Tower, continues to inspire architects today, reminding us of the potential for buildings to rise gracefully into the sky, in harmony with their surroundings.

EXTERIOR, GENERAL VIEW, EAST TOWARDS BUILDINGS COMPLEX - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

EXTERIOR, NORTHEAST VIEW OF COMPLEX - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

EXTERIOR, BASE OF TOWER SHOWING SUPPORT SYSTEM - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

EXTERIOR, DETAIL OF TRANSLUCENT WINDOW, NORTH SIDE, SECOND FLOOR - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

INTERIOR, RECEPTION AREA FROM WEST, FIRST FLOOR - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

INTERIOR, RECEPTION DESK - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

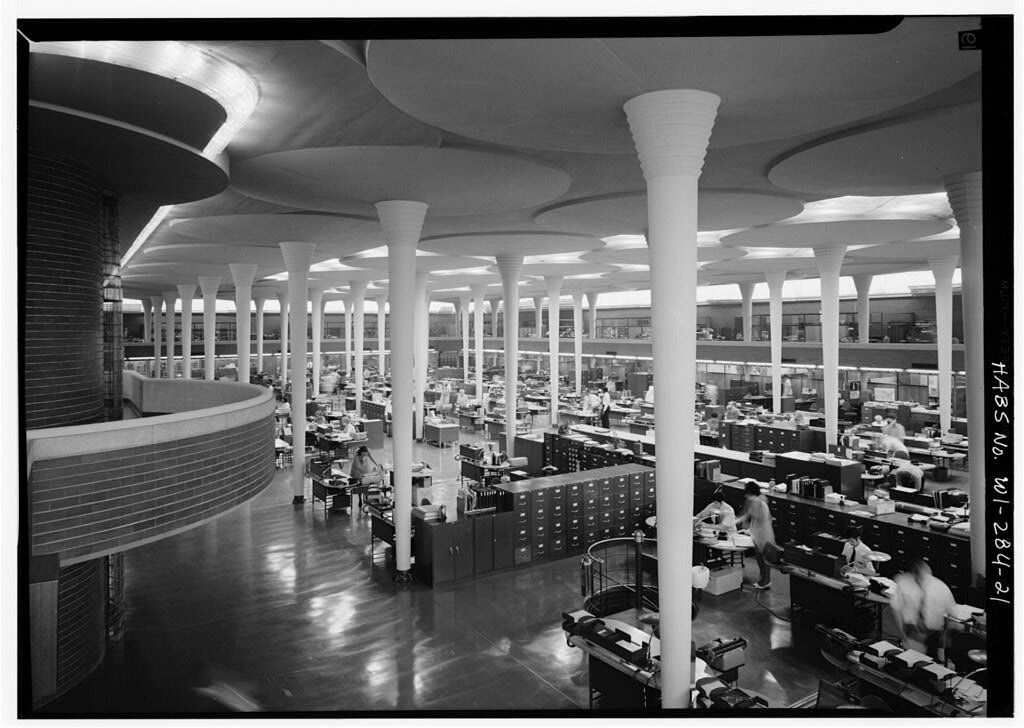

INTERIOR, NORTHWEST CORNER OFFICE AREA, FROM SECOND FLOOR BALCONY - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

INTERIOR, DETAIL OF ELEVATOR, FIRST AND SECOND FLOOR - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

INTERIOR, DETAIL OF SECOND FLOOR BALCONY WALKWAY WITH ELEVATOR - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

INTERIOR, THIRD FLOOR BALCONY AND WORK AREA, FROM NORTH - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

INTERIOR, RECEPTION AREA, EAST VIEW FROM THIRD FLOOR BALCONY - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

INTERIOR, THIRD FLOOR BALCONY, FROM WEST - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

INTERIOR, THIRD FLOOR RECEPTION AREA WITH ELEVATOR - Johnson Wax Corporation Building, 1525 Howe Street, Racine, Racine County, WI PHOTOS FROM SURVEY HABS WI-284

Le Dokhan's, Paris Arc de Triomphe is a luxury hotel located close to the iconic Arc de Triomphe. Guest rooms, restaurant, bar, fitness center and exceptional service are offered but what makes this hotel truly unique is its elevator cab, made from a vintage Louis Vuitton steamer trunk, adding luxury and nostalgia to guest experience. Perfect choice for luxury travelers visiting Paris.