The Solomon Guggenheim’s Lost Glass Elevator

One of the most significant unrealized details in modern architecture.

Detail of Quick Ramp on plan drawing from the 1953 presentation set produced for Harry Guggenheim. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archives, New York, NY. Copyright © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ. All rights reserved. Photo: Kristopher McKay

When one considers a major building such as the Bilbao, Sydney Opera House, Eiffel Tower and so on, it's easy to focus on the grand structure, or the more instagrammable elements within like spiralling staircases, magnificent lobbies, gallery rooms ... in other words, all the obvious architectural spaces. We would argue that right after the reception, a building's elevators are the very next public-facing space building occupants and visitors see, and one architects and designers need to start paying more attention to.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, often referred to as The Guggenheim, is an art museum located in the Upper East Side neighbourhood of Manhattan designed by the legendary Frank Lloyd Wright. A reinforced concrete spiral unlike anything the world had seen secured Wright as revolutionary architect for the third time in his career, and crowned him the leader of modern architecture for generations to come.

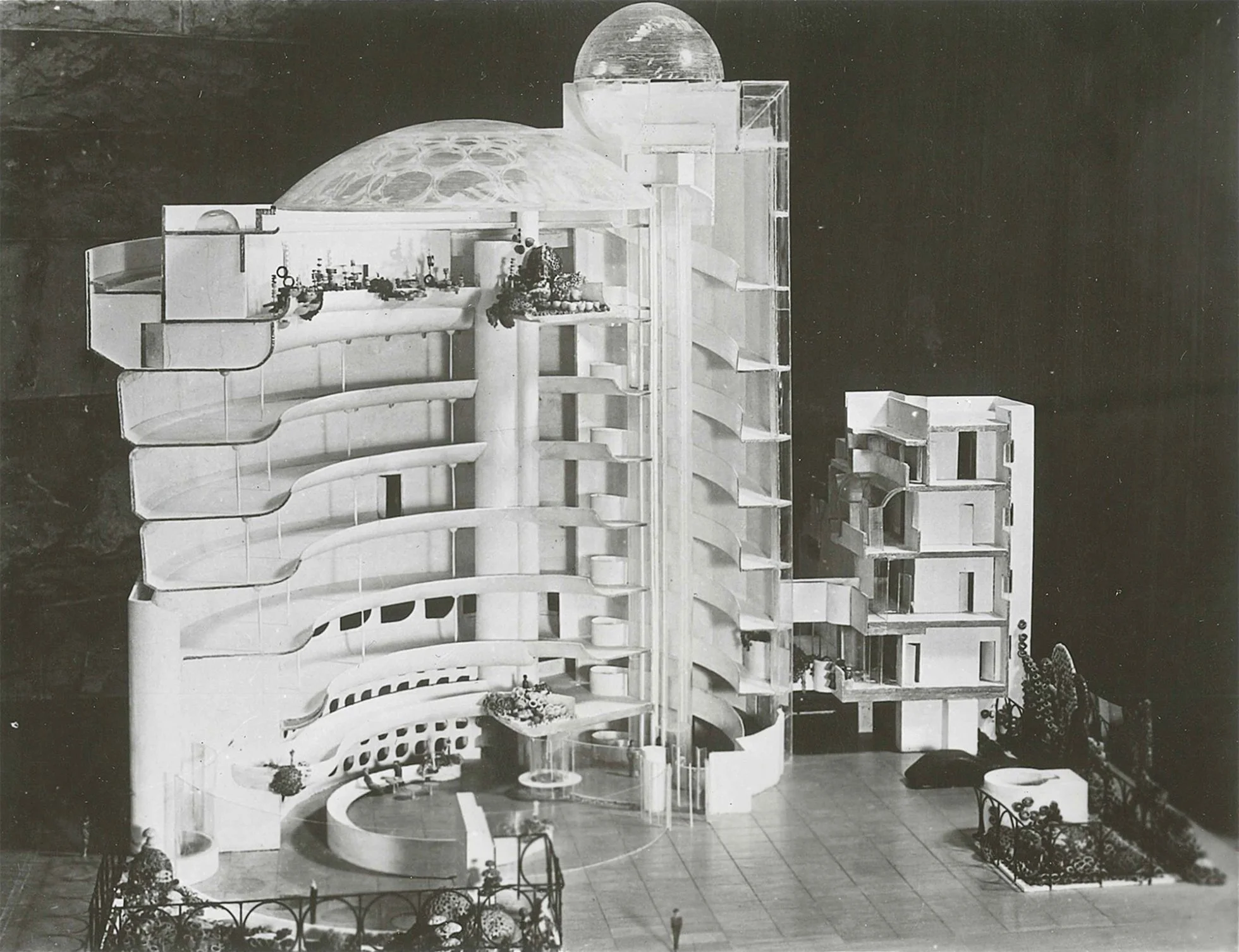

The model was developed and adapted over time. This image from December 1946 shows thin steel columns built in along the inner edge of the main gallery’s spiral. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archives, New York, NY. Copyright © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ. All rights reserved.

The cylindrical building, wider at the top than at the bottom, was conceived as a "temple of the spirit" during a period of transformation in the architectural and art world. Its unique ramp gallery extends up from ground level in a long, continuous spiral along the outer edges of the building to end just under the ceiling skylight. The distance between the Guggenheim rotunda floor to the top of the building measures 97 feet 9 inches.

There are several noticeable differences between the proposed 1945 model and the building as it stands today, including the Grand Dome glass roof over the rotunda inspired by his recently completed Johnson Administration Building in Racine, Wisconsin. However, the most interesting difference is the futuristic glass elevator, shaft and spherical observation deck. In the below image, hidden within the complexity of the model is a custom designed vertical transportation system that would have shuttled visitors up through the gallery.

© Laurian Ghinitoiu (ArchDaily 22 of 30)

As an alternate means of navigating the vertical museum, this distinguishing kinetic-feature would have celebrated the still novel mode of transportation whisking visitors to the top floor, which they would then meander slowly down through the gallery spaces. After an unfortunate round of budget cuts, the museum was redesigned with a standard elevator tucked to the side and far too small to manage the attending crowds. As a result of this design change, most visitors ascend the gallery.

Wright's plan for the museum guests to ride to the top of the magnificent atrium by elevator, then to descend at a leisurely pace along the gentle slope of the continuous ramp, interacting with multiple levels, and to view the atrium of the building as the last work of art before wandering out onto the streets was lost.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hilla Rebay, and Solomon R. Guggenheim standing beside the 1945 model of the Guggenheim Museum. © SRGF Archives, New York. Photo: Margaret Carson

Museum curators typically arrange their shows keeping this in mind. “You cannot get enough people in that tiny elevator,” says David van der Leer, an assistant curator of architecture and design, who worked on a recent retrospective at the gallery in 2018. “The building is so much more heavily trafficked these days that you would need an elevator in the central void to do that.”

While details of the glass elevator are limited to the model and some early drawings, we can only presume that that the birdcage elevators in the S.C. Johnson & Son Administration Building which provided panoramic views of the Great Room traveling from the basement to the Penthouse level inspired the architect when envisioning this vertical gallery.

The Johnson elevators with adjacent tapscot elevator in the Research Tower along with the Price Tower in Bartlesville Oklahoma would be Wrights only built elevators. One of the most iconic buildings of the 20th century, was also his last. Wright died in 1959, aged 91 – just six months before the museum opened in October the same year.

Following its completion, the building has undergone a series of extensions and renovations unfortunately never to include Wrights visionary plan for an all glass elevator moving through the atrium would go unbuilt until nearly a decade later when architect John Portman completed his first dramatically vertical hotel lobbies, the Hyatt Regency in Atlanta, in 1967. The hotel billed the 22-story atrium as “indoor sightseeing.”

Le Dokhan's, Paris Arc de Triomphe is a luxury hotel located close to the iconic Arc de Triomphe. Guest rooms, restaurant, bar, fitness center and exceptional service are offered but what makes this hotel truly unique is its elevator cab, made from a vintage Louis Vuitton steamer trunk, adding luxury and nostalgia to guest experience. Perfect choice for luxury travelers visiting Paris.